A timeless bond: The Queen’s Westminster Rifles and Talbot House

In the autumn of 1915, padre Tubby Clayton gets the task to create a soldier’s club in Poperinge (affectionately known as ‘Pop’ by the British soldiers), a city just behind the front lines. This club was meant to be a warm refuge, where the British Tommies could escape the horrors of war, where ranks were abandoned and where everyone could feel at home. Tubby soon found the perfect location: ‘a beautiful great empty white mansion’ as he described it. On 11 December 1915, Talbot House opened its doors as an ‘Every Man’s Club’.

Building a home together

Adjacent to Talbot House, the Queen’s Westminster Rifles were billeted. This London unit eagerly contributed to establishing the soldier’s club from the very start. Tubby wrote: ‘The Westminsters really adopted the house as their own.’ Together they faced the challenge to turn an empty house into a home.

With the First World War raging, gathering necessary furniture and housewares was no easy task. Tubby described how his right hand, Arthur Pettifer, went scrounging into the city. He scrounged for instance a carpet from a neighbour’s house, which – to his great disappointment – Tubby made him return.

Two Westminsters, Bert Stag and Ronald Brewster, were also present during the early weeks and would later join the staff.

Very soon a piano arrived at Talbot House – even before dish cloths or other basic supplies – perfectly summarizing Tubby’s philosophy: ‘Give me luxuries, the necessities can wait!’ The piano became a central element of the House, remaining significant to this day.

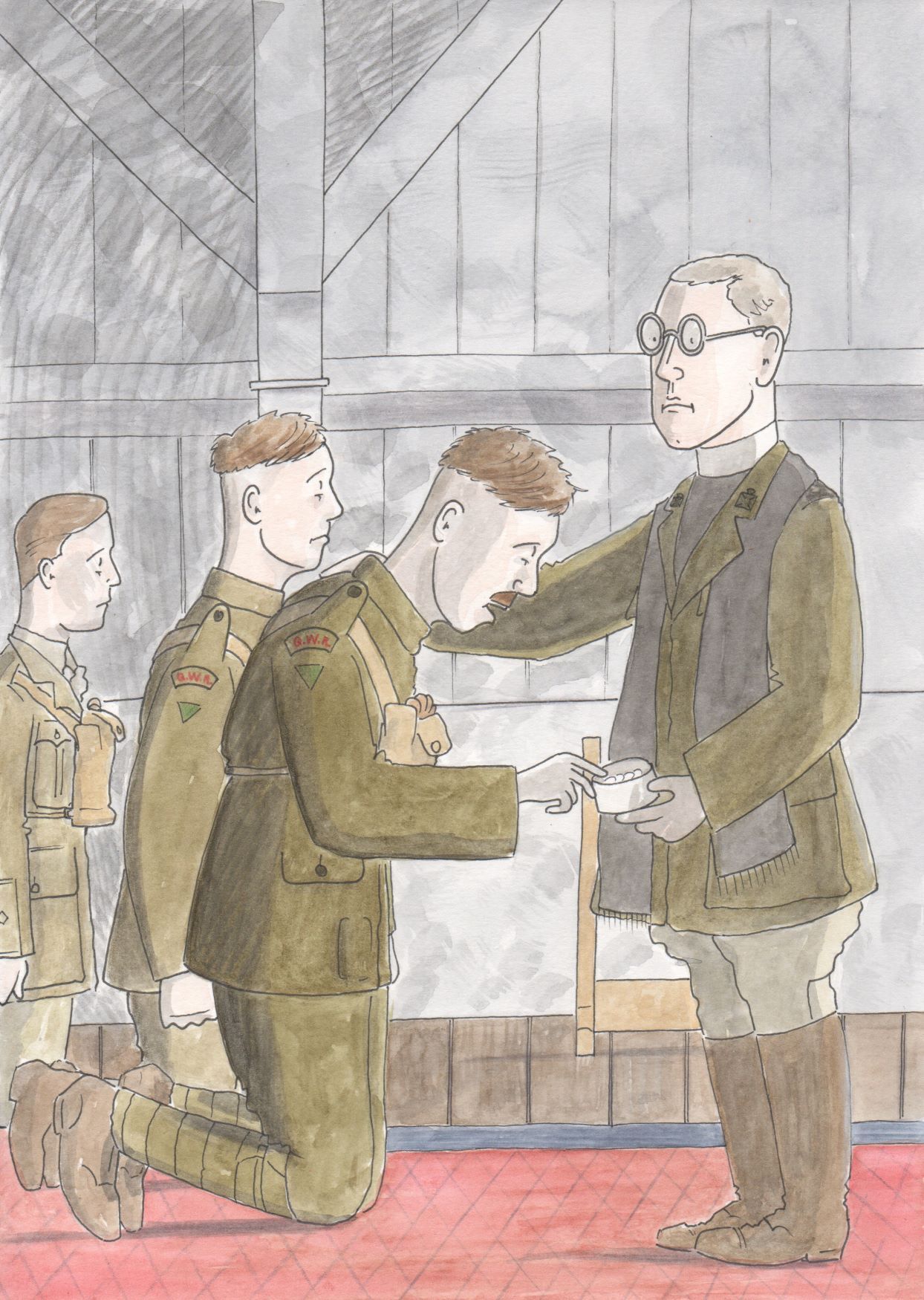

From loft to chapel

The flagship of Talbot House is undoubtedly the chapel, known as the Upper Room. Initially located on the second floor, the chapel quickly outgrew this space and moved to the loft, which Tubby deemed perfect. As he had to be creative, Tubby repurposed a carpenter’s bench from the garden shed as an altar. After all, Josef, the father of Christ, was also a carpenter. Moreover, some more items were added: a blue and white pennant, rescued from the ruins of Ypres Cathedral, some draperies from the private chapel of the Bishop of Winchester, and an altarpiece frame that Bert Stag crafted.

Before the house even became ‘Talbot House’, a German grenade had caused significant damage, which the Queen’s Westminster Rifles repaired. The holes in the chapel floor were covered up with tin boxes and some minor damage to the walls was camouflaged with holly twigs. Thanks to the creativity and the ingenuity of the Westminsters, the chapel gradually took shape.

Celebration and loss

It should be no surprise that the Queen’s Westminster Rifles were loyal visitors to the House. Just a few days before Christmas in 1915, they held an early Christmas service with traditional Christmas crackers! However, the cheer was short-lived. Soon they were recalled to the front line to, among other duties, defend the Potijzestraat after a German attack. They maintained the revelry at the front, wearing paper hats from their Christmas crackers on their gas masks and wielding water pistols filled from bomb craters in defiance and joy.

At their return to Pop, in the night of 23 December, they marched through the streets singing loudly, despite having lost nine men.

The Queen’s Westminster Rifles endured great losses, notably during the summer of 1916. On 1 July, the Battle of the Somme resulted in 600 casualties among the Westminsters. Many of them were wounded, missing or were killed. Bert Stag was also wounded and got medically downgraded. He returned to Talbot House, where he wished to remain as long as possible. He stayed until he was deemed fit again for frontline duty in September 1917, when he returned to his regiment.

Lasting connection

The connection between the Queen’s Westminster Rifles and Talbot House remained.

They donated, for instance, a silver wafer box for the chapel, a lasting memorial for Rifleman Newton Gammon, one of their men, who was killed in Gommecourt. Thus, his memory would live on.

Even long after the war, in 1938, the connection was immortalised with another memorial plaque in the chapel, which they had helped to decorate. With this memorial, they commemorate the period of December 1915 and the strong bond between the Queen’s Westminster Rifles and Talbot House. ‘A connection never wholly lost’.

When The Second World War broke out, this connection resurfaced. Rex Calkin, a former Westminster, and some other Toc H staff were in the North of France to erect Toc H Services Clubs. On 19 May 1940 they visited Pop, to potentially reopen Talbot House for troops. As there were no British troops around, they just stayed the night in Talbot House, went praying in the chapel and signed their names in the register. Later that day, they were taken as prisoners of war.

A lasting legacy

The Queen’s Westminster Rifles played an important role in the establishment and the ongoing existence of Talbot House. Through their creativity and commitment, they, alongside Tubby, created a refuge where soldiers found comfort. Even after the war, the bond between the House and the Westminsters remained strong. They weren’t merely visitors; they shaped Talbot House into what it is today.

Sources:

- Godden, T. (2022). QWR + Talbot House: The story of the Queen’s Westminster Rifles and the Old House in Poperinge.

- Nolf, K., & Louagie, J. (1998). De eerste halte na de hel: Talbot House, Poperinge. Lannoo.

- Louagie, J. (2015). A Touch of Paradise in Hell. Helion & Company Limited.