The Green Book

On 15 December 1915, at 3.30 in the morning, Tubby Clayton, the founder of TH, wrote the following letter to his mother.

Dearest Mother,

Rather an unusual hour for letter writing, even for me – but a certain sphere of the house’s work accounts for my being up to-night. I have just sent my first two weary travellers to bed, after soup and biscuits: this is the opening of our divisional rest-house, to which officers coming and going by trains in the small hours can come and get supper, bed and breakfast.

Tonight, being the first time, I went up to the station and rescued these two from a cold night in the so-called waiting-room. We can accommodate twelve, and shall have the house full every night a week hence, when it is known. Both were profoundly grateful, and were nearly moved to tears by the carpet slippers awaiting them.

When Tubby, a chaplain in the 6th Division, had opened the doors of Talbot House four days earlier, the plan was to run it as a recreation house for troops by day, and a rest house for officers taking the leave trains or coming back from leave during the night. From each officer five francs was demanded for board and lodging, on the Robin Hood principle of taking from the rich to give to the poor. In this way, the contribution by the officers covered the cost of the recreation part of the House for the men, (and a portion of each 5 francs went into the tip-fund of the TH staff).

In Tubby’s words, those were the days of simplicity. Officers slept on stretchers in the former bedrooms of the children of the Coevoet family (who had moved to a safer place) and also on the landing of the second floor leading up to the Chapel. This also meant that those who wanted to attend the early communion service at 6.30 had to be careful not to step on the men trying to get some sleep.

The bedrooms were communal, apart from one room, which was called the General’s Bedroom. Tubby described it in his memoirs as follows:

The smallest room of the House ambitiously was turned into the General’s Bedroom. It just held one bed. That, however, was beyond compare: a genuine, downright, honest and upstanding affair with four legs and an iron frame, even a mattress. What could any man ask more? No one below the rank of a field officer slept in that bed. Majors competed for it, colonels cut cards, and brigadiers insisted that another’s need was greater. We had one pair of sheets that throughout the war belonged to this bed, and the blissful winner was quite free to make up his mind whether he preferred (seeing that one sheet must be at the wash) to sleep above or below the other. (Major Bentinck)

The House went from strength to strength. In a few weeks’ time its scope had extended far beyond the 6th Division. There was room for 12 but on 29 Januari 1916, 26 spent the night at the House. Some slept on the bare floor boards, others could be found half-asleep in chairs until their luckier colleagues got up for breakfast and the leave train. And on the evening of 18th May, Tubby had no less than 76 officers on his hands and over 50 for breakfast the following morning. The staff were almost off their legs, he told his mother. It was clear that the situation had become untenable. In June, Rev Neville Talbot, Senior Chaplain of the 6th Division and co-founder of the House, received orders to extend the work of Talbot House into an Officers’ Club, a daughter-house further down the road. These premises are still known today as Skindles. In August of that year, however, Talbot was promoted and, quite reluctantly, was moved to the Somme, as a result of which, in Tubby’s words, the Officers’ Club became a (spiritual) failure.

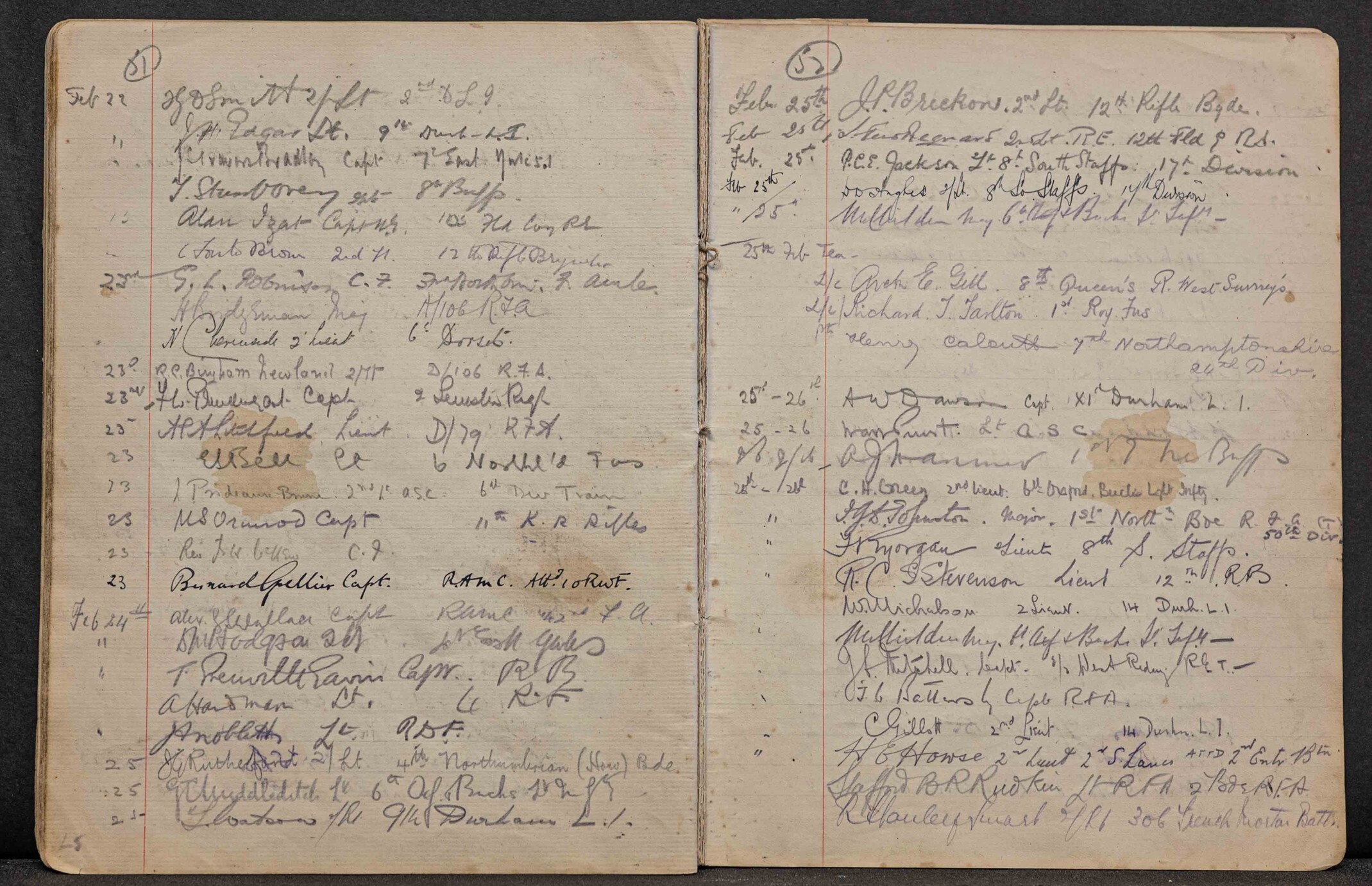

During this very early period when TH acted as a night rest-house, a Visitors’ Book was kept. It was a very simple exercise book (which Tubby had purchased in a local shop), the sort of notebook that was used in primary schools to copy down schoolwork and notes. It had a green cover and became known as ‘The Green Book’. Those who used the House as a resting-place for a night were requested to put their names in it.

“It is one of the many joys of the place that one sees practically everybody in the Salient at one time or another”, Tubby wrote to his mother.

One can indeed safely say that “practically everybody in the Salient” is represented in this book, which was only used from 15 December 1915 till 7 April 1916. During that period approximately 150 military units were in the Salient. No less than 140 of these are represented in the book. The signatures (almost 1,300 in total), mainly in pencil, were produced by 1,093 people. (Some spent 2, even 3 nights at the House). From the records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, we learn that 265 of them (that is 24%) died later during the war. They are buried in//commemorated on more than 120 cemeteries and monuments on the Western Front: 77 of these men in Flanders, 172 in France, 12 in the UK, 1 in Germany, 1 in Ireland, 1 in Italy and 1 as far afield as Tanzania.

Of those who died in Flanders 15 are on the Menin Gate, 12 are buried in Lijssenthoek M.C. (Pop), 6 on Tyne Cot in Pass, and the rest on 26 other cemeteries.

Of those who were killed in France 40 are on Thiepval Memorial, 8 on Arras Memorial, and a great deal more on 73 other cemeteries and memorials.

Whilst helping out at Dressing Stations at the Somme, Neville Talbot saw officers and men coming through whom he had met at Talbot House earlier that year. In their letters to one another, he and Tubby shared names of ‘Talbotousians’ who had been wounded or killed in action. In the meantime Tubby had started a Roll of Honour, which he had put up in the Chapel, adding the names to it of those who hadn’t made it. The Roll is still there.

But from this long list of names also emerge a number of questions. Who were these men ? And what did the war have in store for them ? They might have enjoyed a good night’s sleep, – but what next?

As Tubby put it to his mother:

“It’s beastly shaking hands with boys who come in to say “well goodbye, Padre, in case I don’t come through, and some have such clear premonitions of death”.

This was particularly true of

- 2nd Lt. Charles Tisdall, 18 years of age; he signed the book on 12 February 1916 and was killed the next day, shot by a sniper whilst trying to dig out a young private who had been buried alive during the shelling.

- 6 more were killed within a week after they had spent the night at Talbot House, 2 of them are even buried next to each other at Railway Dugouts Burial Ground (Zillebeke), (Lt. Atkinson and Lt. Edgar)

- 2nd Lt. Edward Hannah, 19, was killed the same day as his brother, Robert, 22 – both are on the Tyne Cot Memorial

- Capt. Claude Dashwood died 4 days after the birth of his son

- Capt. Frederick Smith, who had also spent the night at TH, wrote a postcard to his 7 year-old- son on 25 April 1916 and was killed later that same day. He is buried in Essex Farm Cemetery.

Apart from their signature, some of these men, however, also left behind objects that will forever be linked to their name. Just one example. In January 1916 Major Edmund Street of the Sherwood Foresters came back from leave with a portable harmonium for Talbot House. In the Holy Week of that year, Tubby wrote that 2nd Lt. Godfrey Gardner “played divinely on the groanbox in the Upper Room”. Gardner was organist of the Royal Philharmonic Society and an amazingly good musician. Both Street and Gardner would meet their deaths on the Somme battlefields. Their names were amongst the ones mentioned in the correspondence between Tubby and Neville.

Some of the names in the Green Book are also linked to interesting stories that are still relevant for today’s visitors.

- 7 of those who signed the VB (like Capt. Agate) belonged to the Queen’s Westminster Rifles. They were amongst those who helped transform the loft of Talbot House into a Chapel. In the 3 years that followed, tens of thousands would receive Communion there, some 800 would be confirmed and some 50 baptized.

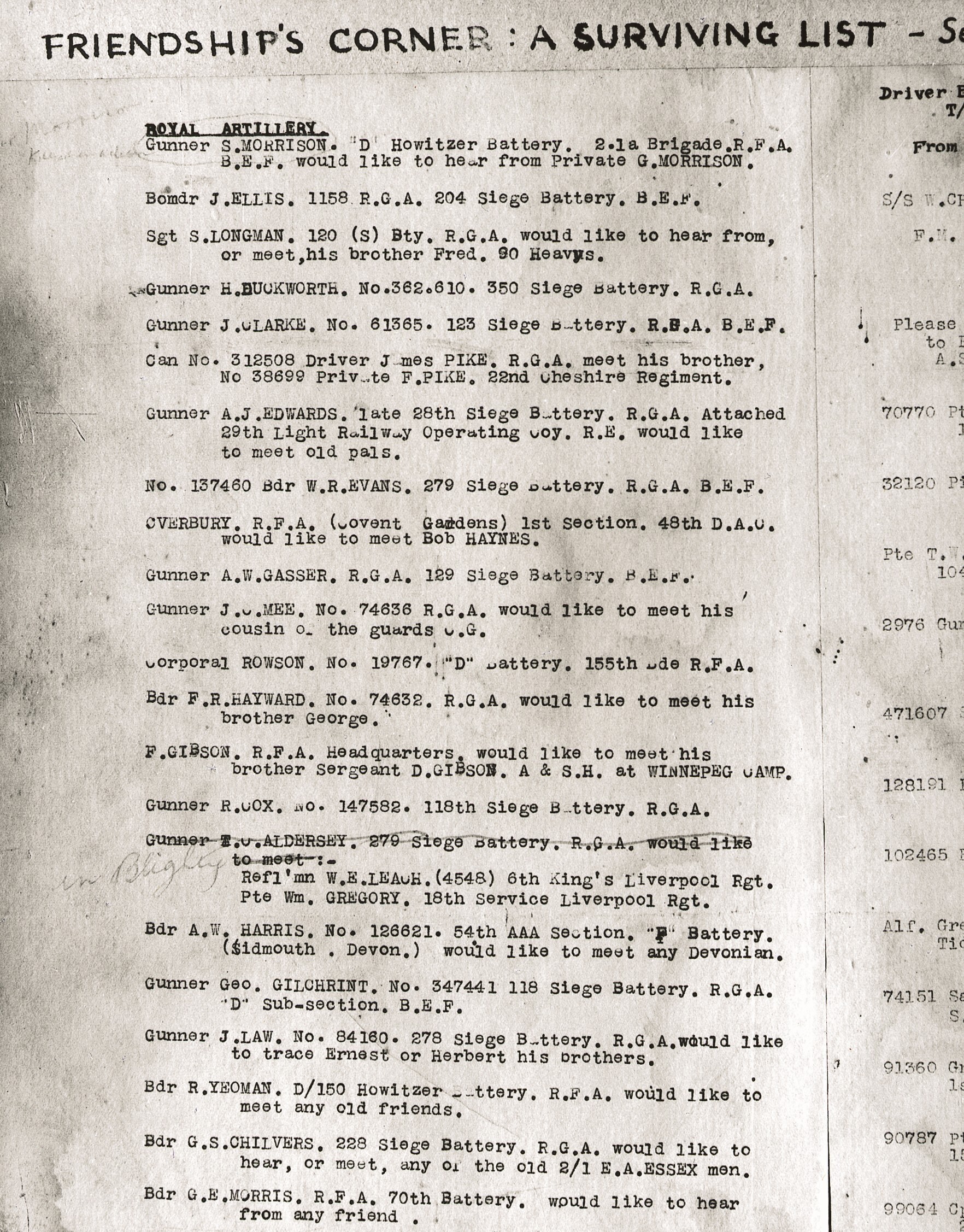

- TH also had a so-called Friendship’s Corner, situated in the entrance hall. There you could add your name to a list and discover where family members or friends were stationed, and you could try to meet up with them. That’s exactly what Bertram and Harold Hubbard did. Both brothers signed the Green Book on 1 April 1916; Bertram would be killed later. Harold, who was a Chaplain with the Guards Division, survived. After the war he was appointed ‘Chaplain to the King’ and would become Bishop of Whitby. In the meantime, we have already identified 9 other pairs of brothers who met up at Talbot House.

Although the initial plan was to allot Talbot House to the troops during daytime and to the officers at night, in reality it didn’t quite work that way. Officers also flowed in during the day, and private soldiers and NCOs also stayed overnight, as the VB shows. In other words, Talbot House truly was, as the signboard proudly proclaimed “Every Man’s Club”.

Its true character clearly shines through the following anecdote from Tubby’s memoirs:

One day I was doing something I ought perhaps not to have been doing, scrubbing floors or something of that kind, in the upper part of Talbot House when Pte Pettifer, my batman, came rushing up to me telling me that a tremendously important General was down in the hall with a sergeant. I went downstairs, hurriedly trying to find the absent parts of my military regalia. When I reached the staircase I found Lord Plumer, the Army Commander. He said to me, ‘Are you Clayton?’ I replied, ‘Yes, Sir,’ He then said, ‘I have got this sergeant here and I want you to look after him for the night, and please remember that he is my guest.’ When Lord Plumer had gone I turned to the sergeant and said, ‘How did this happen?’ The sergeant said to me, ‘Well, it’s like this, padre, my leave came through and I had a pretty desperate time of it walking and had gone almost as far as I could when I saw Lord Plumer. He said to me, ‘Where are you going, lad?’ I said, ‘I am going on leave, Sir,’ The Army Commander then said, ‘You have had enough walking for the time, take a ride in my car; I think I know of a place where I can put you for the night.’

Those who put down their signature truly came from all walks of life:

There were

- novelists like Ralph Mottram and Gilbert Frankau, the latter contributing to the famous trench magazine, The Wipers Times.

- poets like Edward Tennant.

- artists like Claud Fraser (whose work can be admired in the IWM).

- top-class sportsmen, like John Somers-Smith, Olympic gold winner, and also several English, Scottish and Irish rugby and cricket internationals, a boxing champion, an athlete of international repute, and so on.

Others had a wide range of occupations or would continue careers interrupted or postponed by war. Amongst those who signed the Green Book are

- 3 university professors, a famous archeologist, an eminent historian, a well-known architect, & 2 future bishops.

- a great number of medics who were working at the Casualty Clearing Stations in the vicinity of Poperinge: some would make careers as surgeons, psychiatrists or radiologist.

- an Eton College Master and no less than 35 Old Etonians, some of them no doubt his former pupils.

- also several men who would continue their army careers after the war; amongst these 4 later Generals who would all play an important role in the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940.

One can truly say that behind those uniforms were people from the most different backgrounds, from all ranks and classes, from all denominations.

In the meantime all names in the Visitors’ Book have been put into the Talbot House database, together with details about their personal lives, military careers and their connection with Talbot House, as well as photographs. All this information is accessible through the TH website. We also keep files about all those men in our archives. Meanwhile we have also identified more than 3,000 other Talbotousians through other sources, like the Com. Roll. These are all in the database.

But what did become of the Green Book ?

When the night hostel work was transferred to the later Skindles, the Green Book remained at Talbot House. After the war, Tubby took it with him and put it in the safe at All Hallows by the Tower where he had become the vicar. In the hope of attracting more attention and funds for Toc H - the charity he had set up with some of the old Talbotousians - it was decided to put the Green Book on display at the British Empire Exhibition, held at Wembley Park, running for two six-months long seasons in 1924 and 1925 with dozens of buildings and pavilions. Sadly enough, the Book was not seen again - Tubby saying that he almost wept over the loss of it. However, some 40 years later, it turned up again and came back to Tubby who had it photographed. After his death in 1972, it once more disappeared until it was found by coincidence at the bottom of a cardboard box in 2002 and was finally returned to Talbot House, 84 years after it had left. It’s really a miracle it survived.

Not only is the Green Book a unique historical artefact, but, just as importantly, for a great many years it has also been a source of inspiration for all sorts of Talbot House projects: exhibitions, events, concerts, publications, presentations, guided tours, podcasts, blogs etc. In this way we want to make sure that the legacy of the men who left their names in the Green Book more than a century ago, goes on.

That is why we have made an application to the Department of Culture to put the Green Book on the list of ‘Top Artefacts in Flanders’ (Topstukkenlijst). We can only hope that the committee that will assess our application will be open to our arguments.

More than a century later, The Green Book remains a quiet witness to that unique time and those who shared it. Preserving it allows their stories - and the spirit of the House - to continue to speak.

The Green Book

The Harmonium - 2nd Lt. Godfrey Gardner - Major Edmund Street

The Friendship's Corner